Mid-Century Breakthrough: "Third Stream" Music - Page 2

"Gil Evans had been synthesizing similarly with the Claude Thornhill Orchestra in the '40s," notes Maria Schneider, once Evans' assistant and now, at age 49, an award-winning composer, like her mentor, for large ensembles in a jazz context. "The form, the nuance, the orchestration, the color, even much of the harmony [in Evans' work] came from classical music."

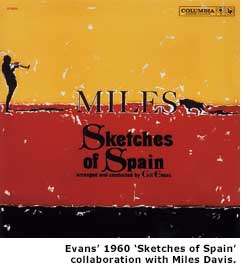

A couple of years after his start with Thornhill, Evans began a collaboration with rising trumpet star Miles Davis. There's a Third Stream affect to their several seminal recordings on the Columbia label, though they're more often categorized as 'Cool.'

Schuller well realized that the roots of his Third Stream concept extended back further still, long before he'd given it a name, to the big-band jazz arrangements of Paul Whiteman and Duke Ellington that he'd listened to while growing up in the 1920's and '30s. And on the classical side, he says, "both American and European composers were wanting, in their varying ways, to incorporate something about jazz in their music."

Having turned on to jazz during a trip to Harlem in 1922, Darius Milhaud exported it to France in his score to the ballet La cration du monde. A dozen years later, George Gershwin created 'Porgy and Bess,' influenced by jazz, blues, and gospel. But it wasn't until 1976 that the work was accepted as opera in America (though Gil Evans and Miles Davis had waxed their own gorgeous take on 'Porgy' in 1958).

Milhaud, who began his seminal stint on the Mills College faculty in 1947, supported jazz wholeheartedly. "The first concert the Octet did," notes Brubeck, "was because Milhaud asked us to play at Mills for the assembly—he was right there."

But, according to Schuller, "Milhaud and [American classical composer] Aaron Copland didn't seem to get the idea of improvisation, and the spontaneity of that, and the idea that that could be done creatively," as he discovered through his dialogue with these two men. "Improvisation," Schuller had realized through his own embrace of jazz, "is really instantaneous composing."

On the other side of the assumed musical divide, there was love for the classics to be found among contemporary jazz giants. "When I met [jazz saxophonist] Charlie Parker in 1952, and he came to my basement apartment to jam, he spent the whole night talking about Bartok and Stravinsky," recalls David Amram, a student of Schuller's and, like his teacher, a French horn player and composer.

Three years later, while playing horn on Mingus's composition 'All the Things You Can C#,' Amram realized that this new creation by the jazz bassist "was a Rachmaninoff prelude and something else that Mingus did—he just put these two things together. With his [Mingus's] extended forms, he had whole symphonies in his mind. He just never had the patience to write them out."

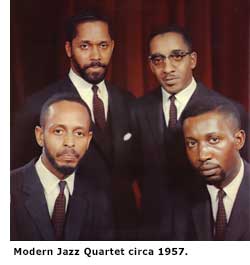

In a 1991 interview, John Lewis and vibraphonist Milt Jackson described how their Modern Jazz Quartet, established in 1952, seemed to personify the tributaries of the yet-to-be-dubbed Third Stream.

"Milt mainly writes tunes and I write compositions," said Lewis. "We're all four of us so different, which is wonderful. I can play your classical music, I can play every note that you [classical composers and performers] have written down.

"But I can do something you can't do: I can improvise on it. You got to play it the same way the next night—I don't have to."

The MJQ evoked chamber music ensembles with their formal wardrobes and restrained, sophisticated arrangements, and thus matched Schuller's purpose of gaining jazz more invitations to the concert hall.

But the dramatic differences between the performance venues for classical music and those for jazz had reinforced their segregation. Classical, of course, boasted much better funding from both the government and white well-to-do patrons; and jazz, aside from big-band ballrooms and producer Norman Granz's atypical 'Jazz at the Philharmonic' program, often had to settle for small, conventional clubs.

But "under those wretched conditions, all this great music was being created and maintained," Amram points out. As Charles Mingus, Amram's occasional employer, once put it, "No matter how ratty the joint, every night with me is Carnegie Hall." The predominance of improvisation over composition in jazz, as Milt Jackson suspected, provided some classical skeptics yet another reason not to accept the Third Stream.