Mid-Century Breakthrough: "Third Stream" Music - Page 3

But, as Dave Brubeck counters, for centuries "it had been traditional for composers like Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven to improvise in their music." In fact, Schuller hoped that the Third Stream might help restore to classical music what he calls "the lost art of improvisation." With that purpose in mind, he, Brubeck, and others of like mind made room in their structured compositions for sections where at least some performers could blow free.

"The really fine improvisers in every culture, including jazz, always come out of grounding and discipline," says Amram, "and at the same time they tune into that magic, unknown world of spontaneity like you see in a great basketball game, or boxing match, or someone on a tightrope."

Amram found that same quality in other areas of the mid-century culture around him, particularly in the free-flowing prose of Beat poet Jack Kerouac, with whom he collaborated at readings and bohemian salons in San Francisco and New York.

For this and other reasons, the '50s and early '60s seemed like prime time for musical exploration. Fred Tompkins, who was then a classically trained reed player in St. Louis, welcomed an expansion beyond jazz conventions, "because when I went to a jazz club, it might be the best jazz I'd ever heard in my life, but I still had this feeling that it could have been even more interesting if it had the broader overall compositional curve that you have in classical music."

"Even in a Mahler symphony," he illustrates, "you can think you're listening to ten different styles of music. Well, in jazz, you didn't have that very much. You had four guys pretty much playing these four instruments for two-and-a-half hours. And as exciting as it could be, I always went home telling myself: that's limited, from a certain perspective."

The success of Brubeck's tricky and delightful recordings and the entrancing discs created by Miles Davis and Gil Evans helped position jazz more comfortably within 1950s pop culture. But jazz itself was craving further evolution, and Third Stream was a factor.

"During the previous decade, which was the end of the Swing Era, bebop had come into full force," explains Schuller. "Then jazz composers like Charlie Parker and Gil Evans started writing their very personal, new, advanced-chromatic music and actually breaking out new formswhich very soon included different sections in different tempos. So all of that made it almost a natural that composition and improvisation would have become much more equal."

Though Parker, Brubeck, and Evans would not have referred to themselves as Third Stream in the '50s, it was easy enough to hang the moniker on the latter two, as well as on composer and arranger Eddie Sauter, who was commissioned by saxophonist Stan Getz in 1961 to write a series of string tone poems against which Getz improvised. The fanciful result, 'Focus' (Verve), is arguably one of the best known and most loved of all Third Stream albums, aside from the Davis-Evans discs.

Later in the '60s, what had been innovative and controversial about the Third Stream became more accepted, familiar, and infused into various aspects of jazz and classical music. It looked like the concept had helped music lovers "realize that [jazz] was really a very serious and creative art form, and that you should respect it," points out MJQ's Milt Jackson.

As the Third Stream concept became more widely clarified, Schuller saw that "it, in its turn, spawned younger musicians to go into both [jazz and classical] fields simultaneously." And Schuller wasn't surprised to see that the term 'Third Stream' itself was becoming a bit outdated and unnecessary. As Schuller's sometime student Amram testifies, "the last thing he [Schuller] wanted was to start some kind of movement. It was just his love of great forms of music, and appreciating what he was surrounded by."

In that regard, Schuller continued his own productivity in the company of creative talents linked to other concepts, such as the blues-based expressionist Mingus and Free Jazz visionary and saxophonist Ornette Coleman. Some of these artists' projects, however—Mingus's 'The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady' (1963, Impulse) and Coleman's 'Skies of America' (1972, Columbia), for example—preserved the Third Stream amalgam of charted and spontaneous music in large ensemble settings.

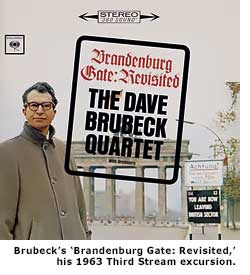

Following the dissolution of his eminently successful quartet, Brubeck worked alongside his lyricist wife Iola on a series of long-form concert hall compositions for orchestra and chorus. Amram went on to compose more than 100 chamber and orchestral works, as well as operas and feature film scores that showcased Third Stream principles to larger audiences.