Cliff May's 'Hacienda Modern'

A few years after Cliff May started winning his reputation by designing ranch houses, he came upon the book 'House of Tomorrow: America's First Glass House.' He was not impressed.

The book included "the most sad-looking group of houses you ever saw," May told oral historian Marlene Laskey in 1982. Laskey's oral history, 'The California Ranch House,' was prepared for the Oral History Program at the University of California, Los Angeles. "There can't be a house of tomorrow," May announced, "because tomorrow never comes."

May, clearly, was no mainstream modernist. He never heard of the International Style until after World War II -- and found it unappealing then. (He was friends, however, with Frank Lloyd Wright.)

But just as clearly, he became one of California's masters of modernism, and not just because his postwar houses are wide-open spaces held up by posts and beams and sided with walls of glass. From his first house to his last, May was a quintessential modernist because of his concern for how a house works. While he may not have been part of the modern movement, May shared its major goal -- using architecture to improve mankind.

A sixth-generation California rooted in all things Spanish Colonial, May won early success in San Diego building hacienda-styled ranches with handmade terra cotta tiled roofs, faux adobe walls, and wrought iron tracery. Soon he was also building the 'ranchera,' similarly arrayed but without the Spanish influence, "so that people who didn't like the Mexican or the Spanish flavor, they had the pure ranch house," he said.

A dapper man, soft-spoken but with rapid-fire delivery, May ran a small office. He was self-taught, and worked as a building designer, not an architect. May did more than anyone to turn the ranch house into America's preeminent postwar housing type. He designed more than 1,000 custom homes -- mostly in California -- throughout the United States, and in Europe, Australia, and the Philippines. May built small subdivisions of ranch houses. And at least 18,000 tract homes were built to designs by May and associate Chris Choate.

May never defined the ranch house through its look. He defined it instead through its function. "It's an informal way of living out of doors," he said. A May house has an open plan, with rooms arrayed in 'V'- or 'L'-shape around a courtyard. In the apex of the 'V' or 'L,' you'll generally find the living room, with bedrooms to one side, and kitchen, dining, and service areas to the other.

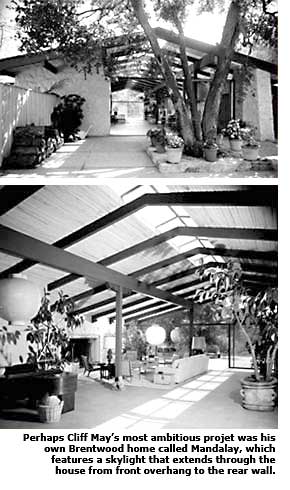

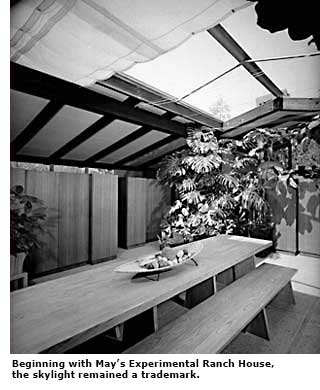

The street-side façade is blank, but the courtyard side embraces the out-of-doors -- in the old days, through large windows, and later, through sliding walls of glass. Between interior and exterior, May ran a 'corredor,' a covered walkway. He sometimes moved the corredor away from the house, turning it into a fourth wall around the patio. The result was a house with an outdoor hole-in-the-center, much like an Eichler atrium.

But what was most characteristic of a May house is its layout. "The plan is what counts," he always said. A May house, except for the smallest tract homes, sprawls across the landscape with subsidiary wings -- often for guest rooms, stables, garages, carports, or workrooms -- appended to the basic 'V' shape. The resulting plan can even look like a pinwheel. "It's like a piece of rope," May said of a typical plan. "You could bend it around and get the absolute best out of it."

May's roofs have broad overhangs supported by rafters that often taper. "The doors can stay open even when it's raining," says Darrell Caraway, an architect who worked with May in the early 1980s. May worked with top landscape designers, including modernists Doug Baylis and Tommy Church, to integrate the houses into the landscape, with lawns reaching the foundations, and mature landscaping of sycamores, birch, and oaks. "The smooth rolling line of the terrain always made his houses look good," Caraway says.

A May house is built on a concrete slab, often with radiant heat, and is on grade. May avoided steps whenever possible -- and avoided grading. He wanted people to be able to step outside without going up and down steps. He called this "ground contact." The best houses, May argued, were built with local materials. He used local stone when possible. When it was not possible, however, May was happy to fake it.