When the Idea of Atriums Was in the Air

|

In 1947, young Berkeley architect Donald Olsen dreamed up a housing type that he hoped would take off due to its utility and sensible planning: a compact house made up of four indoor living areas and four 'courts' to produce “an integrated outdoor-indoor controlled environment.”

Olsen’s courts, which resemble in some ways the atrium that Joe Eichler began adding to his modern tract homes a decade later, were part of a tradition stretching back to the 1920s, scholar Duncan Macintosh wrote in in the late 1960s.

By the 1940s, he wrote, any number of architects in Europe and the United States were building “courtyard homes,” and he suggested why:

|

“Privacy is the key quality of the courtyard house. It looks inward onto a private garden which is as enclosed and intimate as any room of the house. As the source of light, and the connection with the weather and plants, the courtyard is the centre of the dwelling. It facilitates life out of doors because it is sheltered from the wind, free from being overlooked by neighbours, and shut off from the noise of the public world.”

Macintosh, a British author, acknowledged that courtyards and atriums traced back to ancient Greece and Rome, medieval Muslim and Spanish homes, and other historical dwellings, but said that modern courtyard homes did not descend directly from these prototypes.

(However Bob Anshen, Joe’s architect who proposed the atrium, cited the Classical protype, and named the open-to-the-air space an atrium after the Classical space.)

Going back to earlier in the century, Macintosh cited the Arts and Craft designer Gustav Stickley’s “bungalow around a courtyard” from1904, a U-shaped “arrangement which carries with it an association of the old Mission architecture of California,” in Stickley’s words.

|

In California, the Pasadena Arts and Crafts architects Greene and Greene, and architects Irving Gill and Rudolf Schindler designed homes around courtyards.

“The first modern courtyard house was detached and looked south over its private garden,” Macintosh writes, indicating the architect was Hugh Haring and the year 1928.

By the 1930s the European emigree architect Marcel Breuer was designing homes on the East Coast incorporating atrium-like, open-to-the-air spaces, in what Breuer termed a "binuclear" plan. Living spaces were on one side of the house and sleeping spaces on the other, with an open-air court in between.

In 1943 the critic and historian Bernard Rudofsky was recommending patio homes for all parts of the country, not just the milder climes. Apparently Rudofsky expected some resistance to this unusual home plan.

|

“He likened the patio to the early settler’s stockade to give it respectability among those who were still building in the English Colonial style,” Macintosh writes. “Rudofsky even thought it necessary to counter criticisms that the patio was un-American and feudalistic. Nevertheless, he provoked one woman to write a long letter attacking the patio as an instrument for segregating her sex from public life.”

Many modern residences sprung up in California, employing atrium-like center courtyards, including architect John Funk’s home for a psychiatrist in the Berkeley Hills. A beautiful internal garden separated the doctor’s office from living areas, allowing views from one to the other.

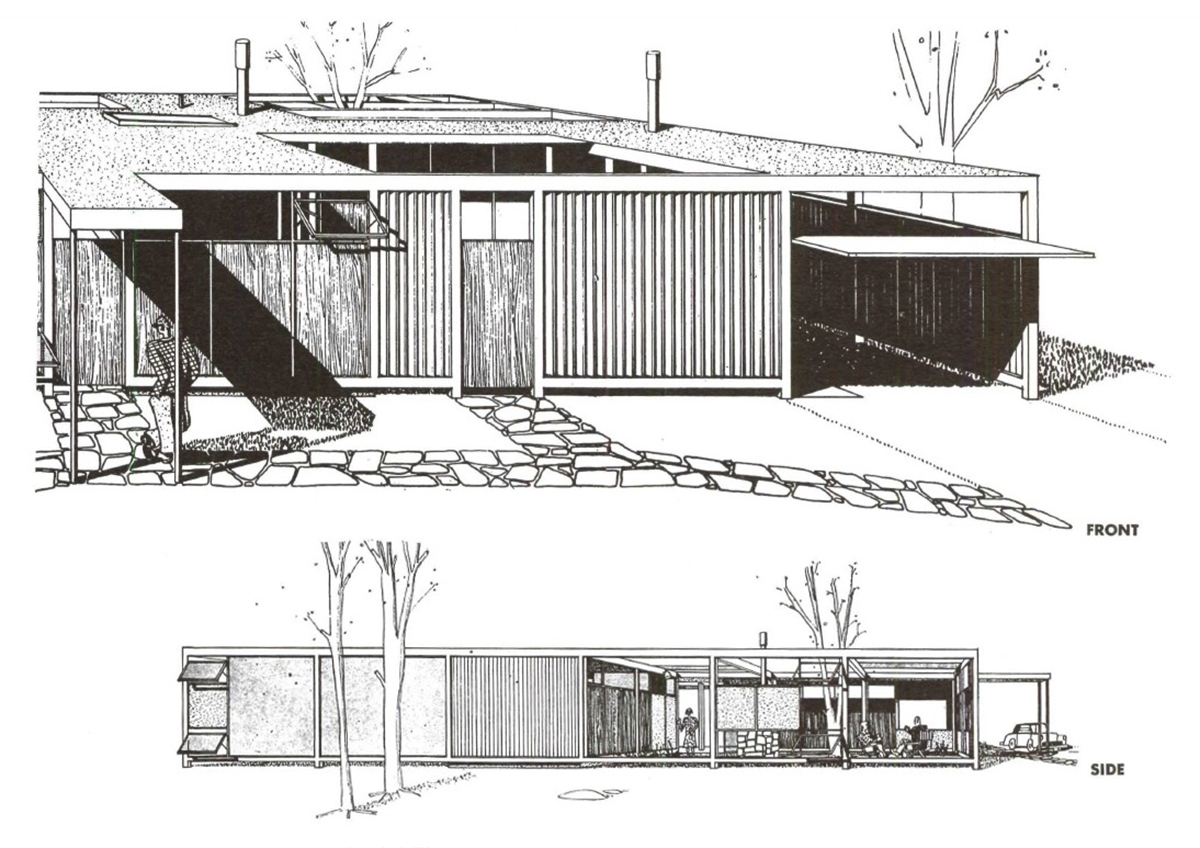

Macintosh cited Olsen’s Contraspatial house, which was published in Arts & Architecture magazine in April 1948, as “one of the first patio houses in the United States which was intended to be terraced rather than be built individually and free-standing.” (In Britain, terraced houses are row houses.)

|

Olsen, who briefly worked for Eichler’s architects Anshen and Allen in the late 1940s (but not designing Eichlers), grandiloquently called his plan the 'Contraspatial house.' Macintosh described it as shaped like a swastika, with roofed spaces alternating with roofless.

Each living space had its own court, the children their own play court, the parents a “sun court.” Main living areas included a roofed but skylighted “family commons,” and an open-to-the-sky “social court which will be used for general family enjoyment, entertainment, barbecue and outdoor eating,” Olsen wrote.

“Sun control is attained by means of movable shuttle canvas-horizontal screens along the tie beams over the courts,” he wrote.

Olsen criticized typical California homes of the period as lacking integration with the out of doors and for large picture windows that led to loss of privacy.

He wrote: “This ‘contraspatial’ house presents one possibility for the development of an integrated outdoor-indoor controlled environment; not a stereotyped house with the addition of large windows and a fenced-in yard but a structure with a functional relationship between each covered (indoor) space and its corresponding controlled open-air space. The house ‘includes,’ not ‘excludes’ these ‘outdoor rooms.’”

• In future posts we will explore other aspects of the history of the atrium – including some pre-atrium Eichler models that have courtyards, and other outdoor spaces that seem prototypes for the outdoor room that came to define the Eichler style.

- ‹ previous

- 640 of 677

- next ›