Cliff May's 'Hacienda Modern' - Page 2

He did not share modernism's horror of copying historical styles, of applied decoration, or of overt romanticism. May was happy to slather on Spanish motifs. May's version of modernism also lacked its theoretical underpinnings -- and its implicit socialism. Americans, after all, don't theorize. They do. And May was far too individualistic to feel comfortable with socialism.

But May's houses were recognized as modern by clients and by his many fans in the popular architectural press. "A house can be modern and not look it," 'House Beautiful' crowed about the Goodrich house in October 1945. Editor Elizabeth Gordon loved the house's "well-engineered" spaces, its use of ramps ("safer and less tiring" than stairs), and its modern conveniences -- including paired husband-and-wife basins in the master bath.

"It's the untutored who still think that modern means flat roofs, stark lines. This ranch house is as modern as molded steel, yet it has been designed of such time-honored materials as board-and-batten, hand-split cedar shake roof. It's not what 'is' used, but 'how.'"

But nothing ties May more closely to the modernists than their shared belief that architecture could improve the lot of mankind. To May the ranch house was not a style, but a way of life. Ranch houses provided a layout -- and a relaxed attitude -- that would enable people to live active, healthful, family-oriented outdoor lives. "People don't know how to live," May complained in his oral history. "People just do not know how to live."

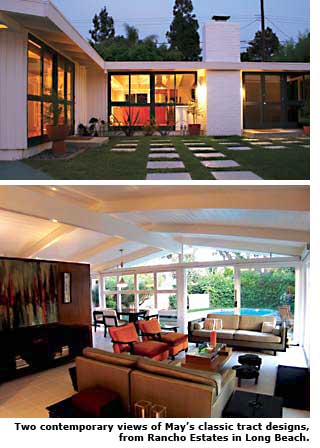

Among May's innovations are many taken for granted today. In the '30s, he moved the garage from the backyard to the street to create more usable backyard space. Also from the start of his career, he oriented the house towards the back courtyard -- a strategy that would be used by California modernists like Eichler in the 1950s.

Although he may not have put much faith in tomorrow, May clearly believed that today needed to be better than yesterday. From the start of his career, he worked to make every house better than the one before. He built five houses for himself and his family during his career, each a series of experiments.

May was attracted to gadgetry. He loved powerful cars and flew his own plane. He loved comfort and freedom from drudgery. May saw the home not as a machine for living, but as an indoor-outdoor mini-paradise.

By 1939 he was equipping his homes with outdoor lighting that gradually turned on as night fell, creating soft, continuous, indoor-outdoor illumination. In 1946 May equipped the family home with an intercom system that let Cliff and Jean May listen in on their kids playing in their bedrooms or patio, a microphone at the dinner table to summon the help, and a gas-fired incinerator to avoid "unsightly piles of refuse." That was one experiment May was glad he tried out in his own home first -- as it almost caught the place on fire.

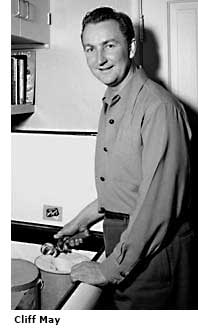

May grew up in San Diego. His mother was part of the Estudillo family, who had been in the state since the 1790s. Cliff spent time with his Aunt Jane Magee ("the lima bean queen of California"), whose ranch included early adobe haciendas.

May drifted into architecture. His first career was the saxophone, and he had success with the five-piece Cliff May Orchestra, performing at the Hotel del Coronado and on radio. Their theme song was 'Thanks for the Buggy Ride.' When the Pantages vaudeville circuit turned them down, though, May turned to furniture making. He manufactured Monterey-style furniture, which he installed in model homes offered for sale by Roy Lichty, who would become Cliff's father-in-law.

Soon, working with developers, May was designing homes complete with tiled roofs, Mexican fireplaces and courtyards. "I built my first house," May said, "and away I went." By the time May left San Diego, in 1937, he had designed about 50 houses. An early client, John A. Smith, convinced May to move to Los Angeles in 1937, arguing that it would be a faster-growing market. They became partners. "People seemed to help young people in those days, not like they do now," May said in his oral interview. "Now, they don't think much of young people."

May hit big after World War II. With GIs returning home, housing boomed. May's homes had always gotten positive press -- 'Architectural Digest' loved them from the mid-'30s -- but he really broke through in the mid-'40s, with long articles in 'Sunset,' 'Better Homes and Gardens,' and 'House Beautiful.'