Did Eichler Homes Imprison Women?

|

The suburbs that sprouted homes like rows of corn in the postwar years often get a bad rap, including from Feminist pioneer Betty Friedan, who in 1963 suggested that the typical suburban home functioned for women as “a comfortable concentration camp.”

Georg Meck, a master architecture student at the Technical University in Munich, is an admirer both of Friedan and of suburban developer Joe Eichler. In a recent paper, ‘Gender Equality in Suburbia and Eichler Homes,’ he examines Joe’s neighborhoods (from afar) to see if they were any better for women than the rather dour portrait he paints of American suburbia in general.

“The typical postwar suburb was a deeply gendered place, and supported by the image mass media had created of the housewife, many women started to suffer what Betty Friedan called ‘the problem that has no name,’” Meck writes.

|

At the root of this deep psychological problem, Friedan theorized, was that women were not encouraged or in some cases permitted to work outside the home, could not forge a life of their own outside of the home, and were devoted to endless tasks of childrearing and housekeeping.

Friedan wrote: “What was the cause of the unhappiness that many middle-class women felt in their ‘role’ as feminine wife/mother/homemaker? This unhappiness was widespread -- a pervasive problem that had no name.”

Many companies would not hire married women at all, many fired women who became pregnant, schools steered women away from studying for professions, and cultural institutions and publications generally portrayed women as homemakers – happy women, that is.

The architecture and site planning of suburbia also contributed much to the problem, Meck writes, citing rows of faceless homes far from civic, business, and social centers; places designed by men for men, and designed to keep women passive and at home.

|

“The power of the built environment kept women in the suburbs, and it separated the space into gendered places. Men were free to move around and to work, while many women didn’t have this principal freedom.”

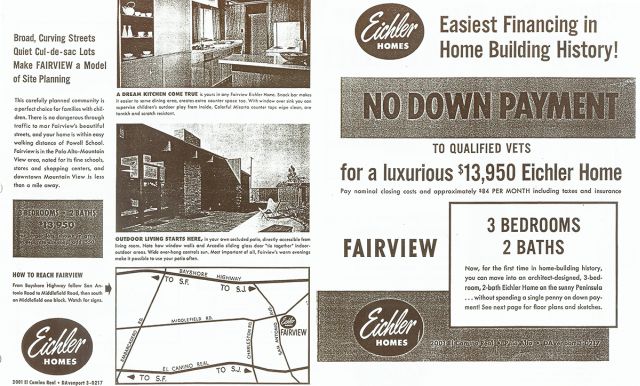

Meck does not note that most Eichler tracts were built within close proximity to a downtown or large business and shopping district.

Meck, who was writing his paper for a seminar on architecture and gender, contacted the Eichler Network this fall to find out if Joe, who was progressive in architectural and social ways, was equally progressive in the field of gender.

It’s clear that Meck hoped so. After describing how most tract developers built nothing but houses and cared not a whit about society or community, he states: “There was one developer, Bay Area-based Joseph Eichler (1900-74), who together with the architects Anshen and Allen, A. Quincy Jones and Frederick Emmons, as well as Claude Oakland, believed that Modern architecture enabled to create a more sustainable family and community.”

|

“A working community requires more than individual lots with identical houses, it also needs premises and common space for a social and public life. Did Eichler and the architects succeed? Were Eichler homes a better place to live?” Meck asks.

“Was there more gender equality?”

When Meck contacted the Eichler Network, these were among his questions:

“Were there many women involved in the company? Or was saleswoman Catherine Munson the only one? Were there any other women involved in the design process, in dividing the lots or in the advertisement?"

“Were the women in Eichler developments also known to suffer the problem that has no name?”

In his paper, Meck cites Munson, Eichler Homes’ treasurer Ruby Rose Germaine, landscape architect Kathryn Stedman, and women designers who sometimes worked for Eichler. But, no, Joe’s was not a company led by women.

|

Munson proved to be more than a typical saleswoman. She went on to run her own realty firm, focusing on Eichlers, and to become an important civic leader in Marin County.

Meck observes that Eichler homes provided space specifically for children, and for women too, as they served as commanders from their perch in the kitchen, allowing them to overlook much of the home and its environs and their children at play.

“Designing more efficient and easy-to-maintain areas certainly help to reduce labor but that doesn’t mean men were equally involved in household labor,” Meck writes.

“I can’t conclude that female residents of Eicher neighborhoods suffered less from the Feminine Mystique than women in other suburbs,” he writes.

Still, anyone who has gotten to know women in Eichler neighborhoods, women who raised kids in the ‘50s and ‘60s, has met some strong and amazing women: women who organized their neighborhoods, volunteered, worked outside the house, created art, ran businesses.

Maybe there was something special about Eichler neighborhoods back in the day that made life for women better: the women themselves.

- ‹ previous

- 148 of 677

- next ›