Kaufmann House

Beth and Brent Harris were architectural tourists, not house-hunters, when they first visited the Kaufmann house.

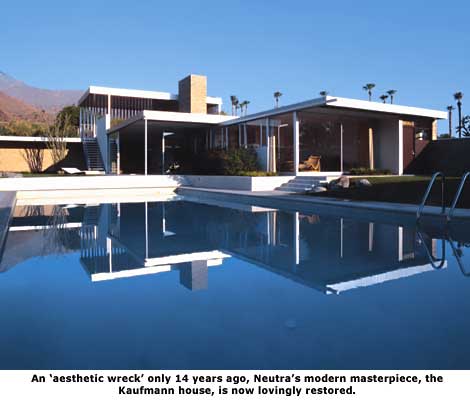

Designed in 1946 by Viennese émigré Richard Neutra, the house was one of the best-known icons of the modern movement, thanks to its striking silhouette, unusual pinwheel plan, remarkable mix of airy lightness and sandstone weight, and the delicacy and precision of its detail.

The house became a part of cultural history thanks to an iconic photo by Julius Shulman that shows Mrs. Kaufmann reclining by the pool like a Greek goddess, the house glowing in the sunset. One of the most-reproduced architectural photographs ever, the photo suggested that modernism is less about machine precision than sybaritic release.

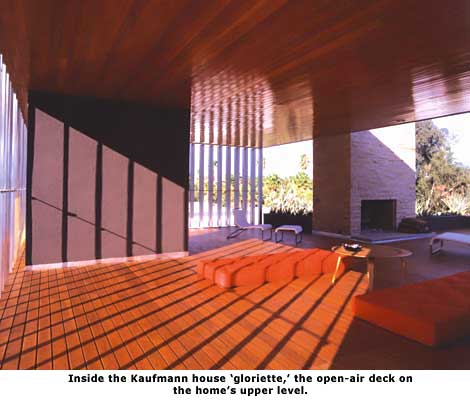

But by the time the Harrises came along, the house was an aesthetic wreck. Originally so open and light-filled that its walls and ceilings seemed more like planes floating in space than enclosures, the house was "dense and dark," Beth Harris says, thanks to 2,200 square feet of additions that turned courtyards into interior spaces. The 'gloriette,' an upstairs, open-air deck that really is one of the house's glories, had its views of mountains and palm trees blocked by air-conditioning compressors.

Neutra's original blond cabinetry, much of the original wall surfaces, and screens of aluminum louvers had been removed or severely altered. Floors were damaged. Douglas fir ceilings had been sand-blasted.

Climate and neglect had also done their part. Beth Harris also blames Neutra's lack of desert expertise. "It's an extremely expensive house to maintain, because everything is exposed. The way it's sited is unusual. It gets a lot of heavy sun."

It was more than pity, however, that convinced the Harrises they had to rescue the house. They could either buy the house, says Beth Harris, an architectural historian who was finishing up her Ph.D. at UCLA, or let it be destroyed. Brent Harris is a managing director of an investment firm.

"We weren't looking for a place to live in Palm Springs," Beth Harris said during a recent afternoon in the home. "We bought the house to restore it. That's the only reason we bought it. To see what it would be like when I was finished. And if we could enjoy it beyond that, that would be the icing on the cake."

"The house had been on the market for four years," she says, "the price had dropped several times, and nobody wanted it."

This was years before Palm Springs came to treasure its modern heritage, and before Palm Springs began its current commercial revival. The broker, Nelda Linsk, a well-known Palm Springs business woman and hostess, had once lived in the house herself and had expanded it by 2,200 square feet. In the late 1980s, Linsk made it clear that she was selling the house, which was then owned by singer Barry Manilow, for its land value.

"We could easily make it more stylish by making it Spanish," Linsk advised the Harrises, "or we could take it down."

"That was really the deciding moment for us," Beth says. "We knew that we absolutely had to get it."

They bought the house in 1993, and by 1999 their accomplishment had become legend, one of the most painstaking and heroic rescues of a modern house anywhere. It was based on a 'philosophy' developed by Beth Harris to guide the restoration, which was to return the house to its original condition, adhering to the strictest historical guidelines.

The architectural and building firm Marmol Radziner and Associates, which had earlier restored Neutra's Kun house in Los Angeles, was soon dismantling the crumbling fireplaces and numbering each stone for reassembly. To repair gashes in the walls of Utah sandstone, the firm convinced the original quarry in Utah to return to a long-closed portion of its site so the color and texture of the new stone would match that of the old.

To find a source for mica, a crystalline sand which workers applied to the house's exterior to provide a subtle, starry-night glow, the architects had to work with the U.S. Bureau of Mines.

The additions were removed, returning light to the interior. Ironically, the additions had been designed by one of Palm Springs' most famous desert modernists, William Cody, a fact not mentioned in most accounts of the house's restoration.