Modern Homes and the California Cure

|

It was an epidemic worldwide and it didn’t last six months, nor a year, but centuries. Called consumption in the 19th century and later tuberculosis, it was a lung disease that ravaged populations, killing at times more people than any other disease.

It was a disease without a cure – but as ever, clever innovators proposed solutions. One of them was – come to California!

“An official [and certainly biased] state health report of 1870 proclaimed California as the ‘Sanatorium of the World,’ ” Lyra Kilston writes in her new, just-right-for-the-times book ‘Sun Seekers: The Cure of California.”

This compact paperback, artfully designed, includes portraits of the Wandervogel of Germany, who took to the hills in search of health, and the “Round dances of the first vegetarians, Ascona, Switzerland, circa 1910.”

|

She also explores the darker side to the quest for a perfectly healthy population, including eugenics and the quest for “race betterment.”

“In Germany, the seeminglybenign pursuits of nude gymnastics, organized hiking and resurrecting old folk songs torque down a sinister path toward war and depravity.”

“Eugenics was considered one of many efforts, like sleeping with the windows open, that would forge a healthier population,” Kilston writes.

But the focus remains on the role played by sharpies, true believers, and modern architects, among others, of our great state.

Kilston writes about, “The myth of California as a cure in itself. A giant natural sanatorium for the revival of the body and the self.”

|

The “sun seekers” who flooded the state from the late 19th on came not for gold. “They sought both physical health and something more holistic and abstract, a source of vitality far from the poisons of civilization,” she writes A” wellspring reclaimed; a return to nature. Some found what they were looking for.”

The mountains attracted some health seekers, the desert others, and many flocked to the sea.

“An ill Massachusetts man wandered the bucolic Ojai Valley with a cow, subsisting only on its raw milk until he claimed a miraculous recovery,” she writes. Observations like this add much to the book’s appeal.

|

There is also great material on such characters as “the Nature Boys,” mostly bearded men in sandals who flitted between LA and Palm Springs’ Tahquitz Canyon to live among the palms.

If you are sitting out today's coronavirus pandemic in the comfort of your light- and air-filled modern home, it may be interesting to hear that health concerns were at the root of the Modern Movement. Kilston notes that many people in the 1920s objected to the coldness of International Style dwellings, with their stark lines and white walls.

“Indeed, at least in its beginnings, the modern house was meant to feel clinical, a clean structure opening toward light, sun and health,” she writes.

“The white wall had an important purpose: to reveal dirt, or rather, to display an absence of dirt – a sanitized surface clean as alpine snow.”

Kilston quotes architectural historian Beatriz Colomina, who puts it even more strongly: “Modern architecture was literally presented and understood as a piece of medical equipment.”

|

Then there’s a guy named Morris Saperstein, out of New York, who attends a talk on vegetarianism, gets into bodybuilding, studies with a magnetic healer, restyles himself as Dr. Philip Lovell, doctor of naturopathy, and moves to California, where he winds up hiring two leading modernist architects to design for himself and his family homes designed to banish all ills.

Rudolph Schindler, who designed the Lovell Beach House, and Richard Neutra, who did the Lovell Health House, were friends and for a time housemates, along with their wives, in a Schindler-designed house with a roof for outdoor sleeping.

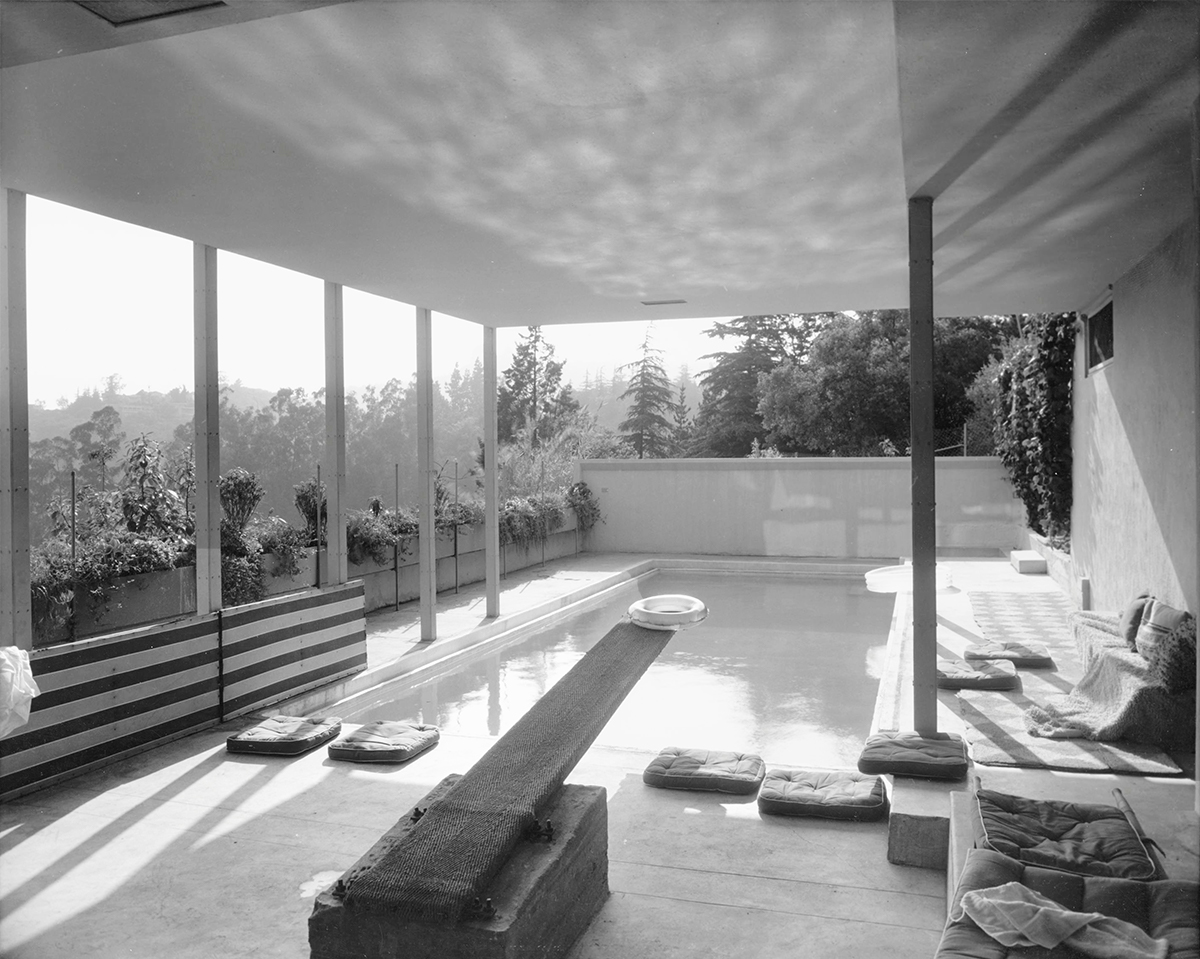

At the Health House (which is currently on the market, for $11.5 million) each bedroom had its own sleeping porch, and there was a built-in swimming pool. Kylston points out there was no chlorine in the pool and no barbecue or cocktail parties on its deck. The Lovells, of course, were vegetarians and did not drink.

There’s great material here on the scene that linked alternate health practitioners with reformist-minded designers. Another character in the book is exercise guru Grace Miller, who had Neutra design for her an ideal living and exercise home in Palm Springs.

As Schindler was preparing to work for Dr. Lovell, he described the home of his vision as something not that far off from an Eichler:

“The house and the dress of the future will give us control of our environment without interfering with our mental and physical nakedness. Our rooms will descend close to the ground, and the garden will become an integral part of the house. The distinction between the indoors and the out-of-doors will disappear.”

- ‹ previous

- 417 of 677

- next ›