Eichler Would Have Appreciated his Renown

|

|

|

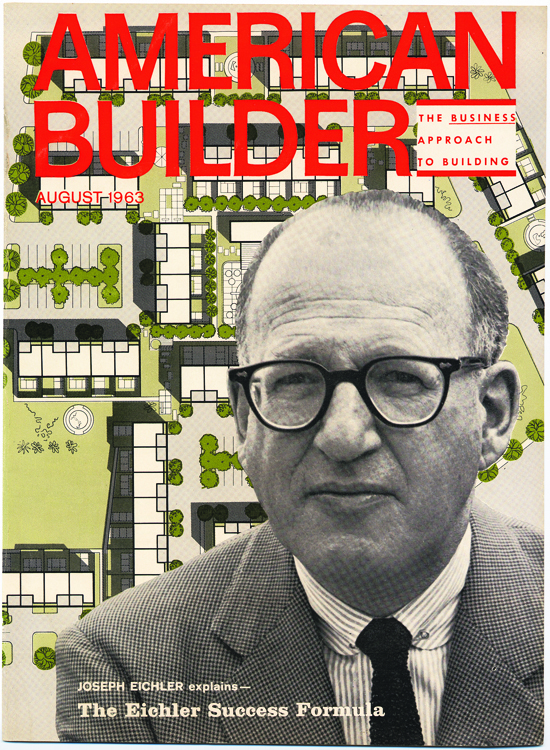

Did Joe Eichler, who died July 25, 1974, ever dream that 40 years after his death the homes and neighborhoods he built would still be adored and that he himself would be regarded as a legend? Probably so.

Eichler, after all, did not go into homebuilding purely as a business. He saw his homes as works of art, well designed and beautifully detailed, places where families could flourish and children could learn.

It is not accidental that the promotional photos shot by photographer Ernie Braun in Eichler homes often showed people indulging in creative hobbies.

Eichler also saw homebuilding as a socially productive activity and he treated it as such. In this way he exemplified the modernist ethos of providing well-designed, relatively modest and affordable homes to a mass market.

He was, moreover, a man with a high degree of self regard, who dressed expensively and well, enjoyed socializing with all levels of society, and had a strong ego, his late son Ned Eichler has recalled. Joe Eichler cared a good deal about reputation.

Homebuilding was a second career for Eichler, after helping run his in-law’s milk and poultry business. Poultry was a career he had not found personally fulfilling. Eichler was pushing 50 when he began building homes in 1947. He got into homebuilding because it was a challenge, a business he could create on his own and run the way he wanted it to run. It was something he wanted to do.

It is worth noting that not only did Joe Eichler build more purely modern homes than any other tract builder in America, he was also one of the very few developers who built nothing but modern homes.

The Alexanders, who built modern tract homes in Southern California, also built ranch-style homes simultaneously. The Streng Brothers in the Sacramento Valley did so too.

And with the Alexanders, mind you, it was the architect, William Krisel, who got them building modern and provided the aesthetic consciousness. The Strengs’ architect, Carter Sparks, played a similar role in that company too.

|

|

|

But Joe Eichler began building modern homes from the get-go, even before he hired any architects. And later, when his own sales people urged him to compromise on the modern designs, Joe would not.

“My father would say, ‘We’re not going to change it,’” Ned Eichler, who worked for his dad in marketing, said in a 2005 interview. “He was willing to put himself on the line, his money and his principles.”

Likewise, Joe Eichler’s decision to sell his homes to black people and other minorities was not about business. He was one of the very few tract developers to build racially integrated neighborhoods before housing discrimination was banned in the mid-1960s.

“For us, [selling to minorities] wasn’t a benefit to our business,” Ned said in a 2005 interview. “We would have been better off if we didn’t do it.”

Ned remembers discussing the matter with a large merchant builder, Larry Weinberg. Weinberg was feeling “Jewish guilt,” Ned recalled, because he would not sell his homes to blacks, afraid that it would hurt his sales.

“‘Larry,’ I said, ‘you’re never going to understand my father. Your whole interest is making the maximum amount of money. That is not his whole interest. You are you and he is he.’”

Perhaps Joe Eichler would be happiest about the way his neighborhoods have retained a strong sense of community. Today, not only are many of his neighborhoods intact in terms of architecture and landscaping, they are occupied by the same sorts of people who first were attracted to Eichlers.

These are people who in the main are aesthetically venturesome, attracted, as was Joe, to elegance. Many of them work in creative fields or are otherwise inventive. They make companionable neighbors.

|

|

|

- ‹ previous

- 202 of 678

- next ›