The Architecture of … Alfred Hitchcock?

|

Does your favorite building have star power?

Is it attractive? Sexy? Alluring? Does it have enough stage presence to stand its ground next to Cary Grant, Eva Marie Saint, or Janet Leigh? Enough personality to attract fans, and friends who will pitch in when things get tough?

Christine Madrid French knows a few buildings like this.

A film scholar, architectural historian, and screenwriter, but mostly a preservationist, Chris French learned an important lesson in preservation from Alfred Hitchcock: For people to love a building, for people to want to save it, it helps if that building comes alive like a character on the silver screen.

Throughout the summer, the California Preservation Foundation, where French works as development and marketing director, is putting on a series of Zoom events, dubbed ‘Modern|ist,’ aimed at both preservation professionals and the general public.

|

Most of the events aimed at the latter are free; none of them cost much; all can be viewed afterwards on the foundation’s Facebook page.

French’s talk, ‘Alfred Hitchcock and American Modernism,’ happens Thursday, Aug. 20 at 5:30 and is free. About Hitchcock and architecture, she quotes another writer on Hitchcock, Steven Jacobs, that “designing architecture is a Hitchcockian activity” critical to his art.

The first talk by Alan Hess was June 18, ‘What Is Modernism and How to Save It?’ Upcoming events include:

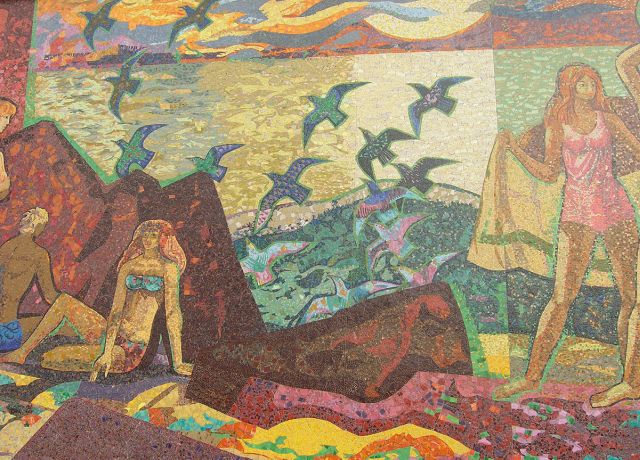

‘Capturing Modernism,’ with architectural photographer Darren Bradley, July 30, at 5:30; ‘Saving the Seventies,’ with Greg Castillo and Michael Toivonen, Aug. 26, at noon; ‘Neuroscience, Architecture & Richard Neutra,’ with Barbara Lamprecht and James Wise, Aug. 11 at noon; and ‘Millard Sheets and Home Savings: Mid-Century Modern Architecture for Corporate and Urban Identity,’ a pre-recorded program, available free through August.

|

As an architectural historian, French was principal investigator for a report on Florida’s mid-century modern places. She co-founded an advocacy group dedicated to saving buildings of the “recent past.” She worked on the same topic for the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

As a film scholar she wrote a paper, ‘American Modern Architecture as Frame and Character In Hitchcock’s Cinematic Spaces,’ and is turning it into a book that should be published in a year or so.

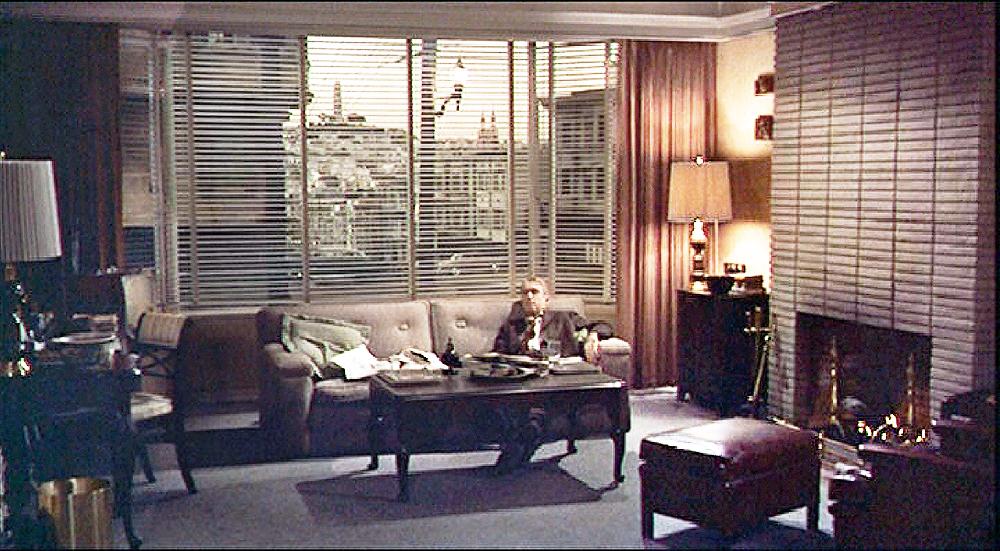

French says she learned some preservation techniques by going to the movies. She focuses on Hitchcock's films ‘Psycho,’ ‘Rear Window,’ and ‘North by Northwest’ as films that show the director's use of buildings as characters as well as settings.

Yes, they are settings, she writes. “But the buildings can be employed to serve a sentient purpose as well – to capture and convey feelings, sensations, and moments that generate an emotive response from the viewer.”

|

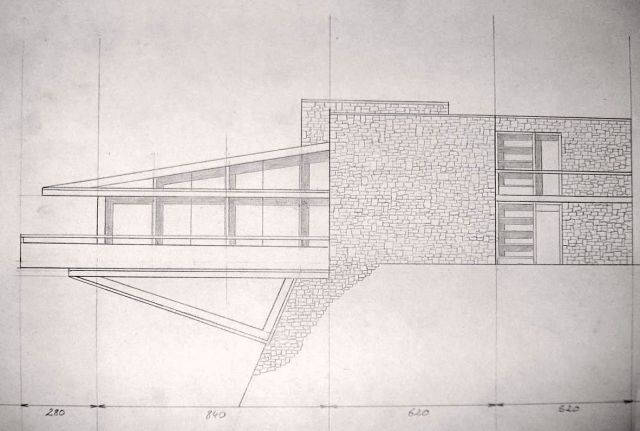

Remember the Vandamm residence in 'North by Northwest,' with Cary Grant climbing the exterior beams to toss a matchbox at his girlfriend, Eva Marie Saint, to save her from the fiendish James Mason?

That gorgeous Wrightian house was no house at all, but a movie set. Yet it talked to people as a character would.

“These buildings,” French says of the Vandamm house, the Bates Victorian home in ‘Psycho,’ and several others, “have their own websites, their own fan clubs.”

“The Vandamm house is actually famous, even though it was not a real place,” she says. “People love the house. Someone in Australia actually built a copy of the house.”

One of French’s successes was helping save the Capen house, an 1885 mansion in Winter Park, Florida, a proposed teardown.

“We had to cut it in half to move it. I called one side Fred and the other Ginger, after Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers,” she says. “It provided a character to the house. People loved it. The press loved it.”

|

The question was, “How can we give it character? How can you make the public pay attention to a historic building?” French says.

Her study of Hitchcock, she says, “started out as historic preservation. I was trying to understand how these buildings from the Hitchcock movies were so compelling to people. I started with the 'Psycho house.’ People recognize it right away, though it is not a real building.”

“When you are talking about a [Richard] Neutra building, more people will get involved if you say, it’s the building that was in 'LA Confidential.' Or if you’re talking about [John] Lautner, and you mention his homes were in the James Bond movies,” she says.

“You can use the same methods used by screenwriters, directors, and producers to make the building a character. How did they change these buildings into characters in the movies?”

“It’s a preservation marketing tool,” French says, adding “It’s a way of getting people to understand where you’re coming from.”

- ‹ previous

- 560 of 677

- next ›