Playing With Space - Page 2

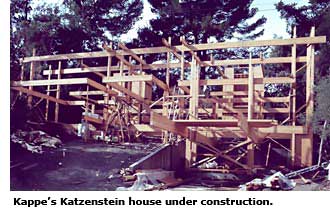

"That was his real innovation," says Ray's son Ron, who runs the architecture firm Kappe + Du in San Rafael. The system proved particularly useful given the challenging slopes Kappe usually confronted. Kappe built a handful of homes using this system, "where applicable," he says.

Kappe's homes continued to be largely modular -- based on sections of uniform dimension -- but often didn't seem so because of their spatial complexity. Modules of regular dimension are conducive to prefabrication, which is what the architect had in mind. The goal, Kappe wrote in the catalog 'Ray Kappe: A Retrospective,' a 2003 exhibit at the A+D Museum in Los Angeles, "was to develop pre-wired, pre-plumbed insulated panels that could be inserted between structural supports much the same way glass is inserted."

What does a mature Kappe house look like? The 1965 Pregerson house, the last of his post-and-beam houses, sits on a level site but floats above it nonetheless to avoid flooding from the neighboring brook.

Though small and simple in plan, there's plenty of excitement thanks to clerestory windows that create a high-ceilinged living room, a raised, Japanese-style walkway that surrounds the living room, the rhythms created by open beams, warm woodwork, and a soffit in the living room that creates a sense of shelter.

Kappe's own house, 4,000 square feet and built in 1965, in wooded Rustic Canyon in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Pacific Palisades, shows his style in full flower. A Kappe house, you notice immediately, can be aggressive. It reaches out with immense cantilevers -- in this case, a floating deck over the carport.

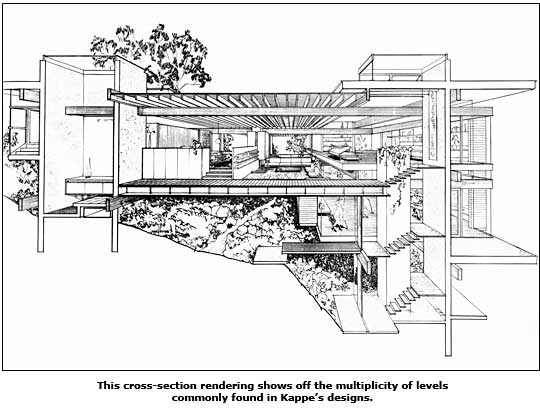

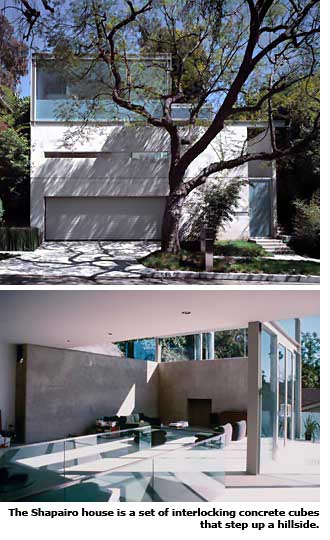

Kappe clearly appreciates outdoor living. Many of his houses step back a hillside, forming several levels of roof -- none of which he forgets. "If you have a roof," he says, "you have a deck."

Kappe is also aggressive in his use of texture, using rough wood arranged to emphasize variations in color and texture, and thick laminated beams that contrast with walls of glass.

Kappe uses slats to create rhythm and shadows -- slats in his balustrades, the slatted effect created by beam-ends, and slats holding up skylights. Slats of light-colored wood alternate with slats of dark to create a characteristic piano-keyboard effect on stairs.

Effective use of 'unbuildable sites,' as they once were called, is another Kappe characteristic. Kappe takes advantage of the sites in an aesthetic as well as practical way. A creek runs downhill beneath the Kappe house, which floats above it on piers.

And the very structure of a Kappe house -- one elegant floating plane above another, a scheme that is consistent both outside the home and inside -- allows him to avoid the clumsy 'house-sitting-atop-an-ugly-substructure' effect that makes so many hillside homes blots on the landscape.

"My complexity comes in section," Kappe says, "not from the plan. My plans are pretty basic." By section, architects mean a building seen from outside as though a surgeon's scalpel had removed the walls.

Many modern architects erase the boundary between indoors and outdoors -- but few with as mesmerizing effect as Kappe. His mitered glass-on-glass corners, many of which project from the house as bays, can play tricks on the eyes. Is that greenery we're looking at inside the house or outside?

Kappe's most explicitly Arts & Crafts home, the Keeler house, combines the warmth of a bungalow with Kappe's characteristic drama. A skylight runs along the home's spine, illuminating several floors at once, thanks in part to translucent glass floors. "People laugh that I try to pretend this house is a bungalow," owner Anne Keeler says.

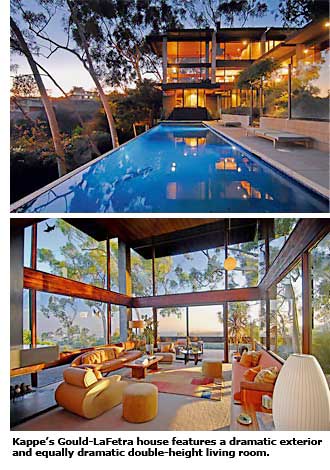

There's a sense of adventure as you move through a Kappe house. First you drink in its dramatic exterior, then wonder: how do you get inside? At the Gould-LaFetra house, it takes some looking. "That's part of the journey of discovery," says Shelly, an architectural historian and Ray's wife of 58 years. "You really need to puzzle out where the door is."

The Gould-LaFetra house has a dramatic, double-height living room, which contrasts tellingly with the low-ceilinged bedroom that floats above and looks down upon it. Kappe understands the psychological need for intimacy. "It's great for bedroom talk," he says.