Mid-Century Jazz: Listen to the Cool - Page 3

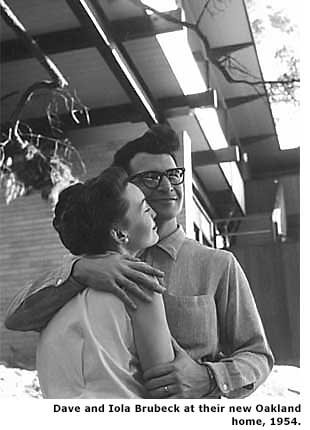

Iola detected musical elements in those plans, what she calls "a definite visual rhythm, a broad expanse which is broken into by the beams." When she, Dave, and their growing family took occupancy in 1954, the new home inspired the creation of music. The spacious glass windows provided sweeping views. The anchoring boulder, incorporated into the interior design with a table of tempered glass across its top, served as a kind of giant touchstone.

"I had a nine-foot grand [Baldwin] piano right next to that rock, and many of the most famous things I've written were written there," says Dave. "And the 'classic' quartet, with Paul Desmond and Joe Morello [and sometimes Eugene Wright, the only one of the four not based in the Bay Area, but in Chicago], that's where they did all their rehearsals." A recreation space laid out after the Brubecks' acquisition of an adjoining lot was the setting for a session of basketball with a visiting Miles Davis.

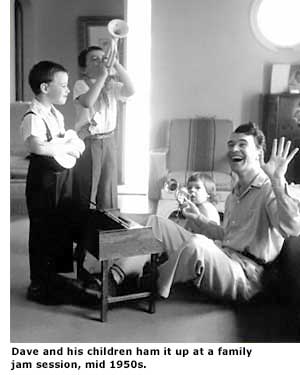

"With small children, it was a bit of a challenge keeping it quiet for Dave to work," admits Iola. A large sliding door, seaweed panels, and cork floors helped to contain the sound of working musicians, but couldn't block their sons' bourgeoning curiosity. "As they grew older and more interested in rehearsals, they would hang around," says their mother. "They saw people having fun playing."

That four of the Brubeck boys ended up as professional musicians may have had something to do with their childhood home's mid-century modern design, "because it was very open," says Iola. "And this was the '50s, a period of togetherness."

The broad commercial success of the Dave Brubeck Quartet, with albums like 1959's 'Time Out' (created "next to that rock"), eluded most other jazz artists in the 'cool school' or any other genre of jazz. An exception was San Francisco pianist Vince Guaraldi, who placed on the pop hit parade with his blithe air, 'Cast Your Fate to the Wind,' in 1962. Another crossover at about the same time was sweet-toned saxophonist Stan Getz, a sometime Southern California resident who became associated with, and handsomely rewarded by, the percussive pandemic of bossa nova, which was imported from Brazil and very accepting of 'cool' players.

A decade earlier, Los Angeles immigrant guitarist Laurindo Almeida had already helped implant samba rhythms and breezy Latin percussion into the West Coast scene. In the Bay Area, after Cal Tjader departed drums and the Brubeck trio, he focused on the vibraphone and his own several groups, and on a sophisticated—and cool—approach to what would come to be called Latin Jazz.

In a personification of the bicoastal jazz trade, sax titan Sonny Rollins headed to Contemporary's Los Angeles studios to record his Way Out West album in 1957. Tripping on his temporary reprieve from the New York City lifestyle, Rollins posed in a cowboy hat and holster for the LP's cover shot by photographer William Claxton. The album's relaxed and sometimes humorous style and its employment of two of Los Angeles' busiest players, drummer (and later club operator) Shelly Manne and bassist Ray Brown, suggest Rollins' recognition of the influence of the west. The title track was included in Contemporary's 'West Coast Jazz Box,' but the album itself was actually a multi-genre national best seller.

Southern California jazz musicians in the '50s and '60s not blessed with widespread recognition had to look outside their choice small ensembles for financial reward. Studios demanding film and television soundtracks provided more and more work during those decades, bolstering the coffers of talented and flexible bandleaders, composers, and arrangers such as Benny Carter and Bill Holman. They in turn were able to offer instrumentalists sometime employment in their big bands, which, despite their expansive size, showcased cool elements in arranging and soloing.

Holman describes his approach as inspired by "imagination, not getting hung up in big band rhetoric." In a recent interview, he set out his approach in terms of what might sound like West Coast Lovemaking. "The most obvious thing is shape," he said, "and the most obvious point of that is not getting to a climax too soon. Because some guys, when they write longer charts, they get to the climax a couple of choruses into the chart. And from then on, it's just hovering around the same climax, neither surpassing it nor fading out."