Home-Run Pursuits: Working at Home the Modern Way

When sculptor Tony Natsoulas decided it was time to relocate from an inner city warehouse to a real home, he knew it had to include a studio.

When sculptor Tony Natsoulas decided it was time to relocate from an inner city warehouse to a real home, he knew it had to include a studio.

"I like working at home. I like going out to the studio anytime I want instead of going across town," he says. "If I get a whim at two o'clock in the morning, I can sculpt."

Tony and his wife, Donna Natsoulas, chose a light-filled Streng Bros. home in North Sacramento, turning its garage into a studio and the rest of it into a virtual museum of California Funk.

It's turned out to be an ideal place to work, providing enough room to construct his larger-than-life figures and to run two kilns. The garage also makes it easy to load his work onto trucks. Plus, he's made friends. "Tony has the garage door open, so he knows all the neighborhood kids," Donna says. "Kids come in and make things with clay."

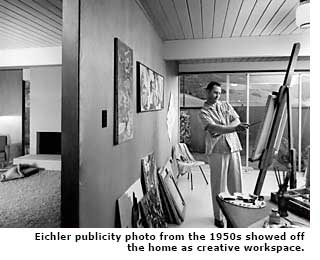

Modern homes attract creative people, so it's not surprising that many are used for creative businesses. Many creative people who run businesses from modern homes say the homes inspire their designs. Others appreciate the flexibility the homes provide. Some even say that without the home, there would have been no business.

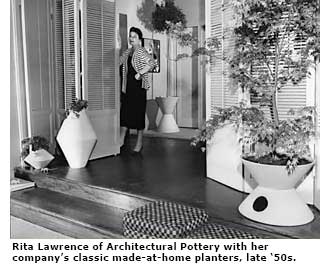

That's what Rita Lawrence said about the business she founded in 1950 with her husband Max. Architectural Pottery won fame for its simple, starkly beautiful planters. It became one of the best-known producers of modern ceramic and plastic furnishings in the country—and, no doubt, one of the best-known artistic endeavors ever run from a modern home. "We wanted to "produce the classics of the future," the Lawrences vowed. They succeeded.

The firm got its start in a compact 'Modernique' tract home in Los Angeles' Mar Vista neighborhood designed by Gregory Ain.

What inspired the Lawrences to produce modern planters? "I think in truth it was from living in Gregory Ain contemporary housing," Rita Lawrence told an oral historian in 2000 ('A Better World Through Good Design,' an oral history conducted by Teresa Barnett for the Oral History Program at the University of California, Los Angeles). "Because when we went out to try and buy anything from a lamp to an ashtray to furniture, there wasn't anything (that would fit the house)."

The Lawrences, socially conscious as well as obsessed with cutting-edge design, did more than live in an Ain home. They became Ain's angels, financially backing several of his projects. They lived in his Dunsmuir Apartments in Los Angeles, and briefly at a cooperative project Ain designed in Altadena.

"We came to be called Ainal erotic," said Rita, who dated Ain once, long before she met Max. Ain concluded the date by taking her to see one of his houses.

Although the home in Mar Vista was only 1,200 square feet, it worked well for the business. "It was a house that you could make function in any number of ways. In that, we ultimately had wonderful usage," Rita said.

The house had a pass-through between galley kitchen and open living area, where a high school boy she hired as secretary set up his typewriter. A foldout door separated the living area from a room the Lawrences used as their master bedroom at night. During the day, the room was filled with pots and paperwork. The two back bedrooms were occupied by their son, Damon, who was seven when Architectural Pottery began, and daughter Diane, "a tranquil little roly-poly of six months."

Neither Lawrence ever threw a pot. Instead, they worked with young designers Max met at Los Angeles' Chouinard Art Institute. The ceramics were outsourced to an old-time terra cotta firm.

They sold less to stores than to architects and interior designers who needed modern objects for their projects. An early customer was Frank Lloyd Wright. Rita remembered when a department store executive from St. Louis stopped by. "I think he expected a business, and I think I was in my mommy's dress and my baby crawling around." Still, she said, he placed "an enormous order."

Within a few years, however, the house proved too small, so the Lawrences moved to the high-toned neighborhood of Bel Air. "We found this place, and it seemed to answer everything we wanted, except the design," Max recounted. The house was Spanish. The Lawrences wanted modern—and they got it, by bring in designer Hendrik Van Keppel, of the firm Van Keppel-Green. Van Keppel opened the home to the out-of-doors, provided a glass-walled atrium, and modernized the interior.

Rita continued to run the business from the home, using the atrium to display her wares, and working with her staff around a large Van Keppel-Green table. Max, who retired from canning in 1958, was soon working alongside his wife. Even as the firm expanded, creating large fiberglass planters for malls and furniture for airports, the Lawrences ran it from their home.