Soundtrack for Modern Living: Esquivel in Orbit

In Southern California of the late 1950s and early '60s, there was attention not only to the look of modernity—in homes, cars, clothing, and beyond—but also to the sound of it.

The Los Angeles studios and sales rooms of RCA Victor Records were abuzz with the introduction of what the company termed 'Stereophonic Orthophonic High Fidelity,' a dramatic improvement over the monophonic, or one-channel, recordings which had been the mode ever since Nipper the Dog, RCA's long-standing label mascot, had started listening to 'His Master's Voice' a half-century earlier.

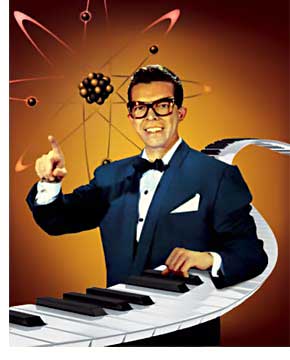

In the mid-1950s, RCA imported a composer and arranger from south of the border, Juan Garcia Esquivel, and set him up in L.A. to record an album, compatible with both old mono and new stereo systems. Esquivel, at this point, was unfamiliar in the U.S., though he'd gained notice as a pyrotechnic pianist and writer of music for radio in Mexico.

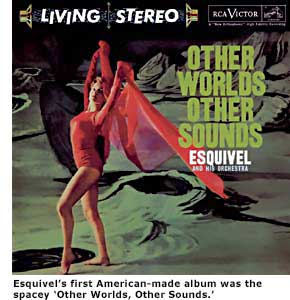

But Esquivel made the kind of music that would make folks go out and buy stereos—just for the thrill of hearing him deliver the new dual sound with maximum effect. His first American-made album for RCA, 'Other Worlds, Other Sounds' (1958), radiated the post-Sputnik spirit of the times, with a tightly clad, ethereal female on the cover, posed amidst lunar craters. Inside were equally spacey musical arrangements, applied to familiar American pop and Latin tunes but in a manner that highlighted the advantages of listening to two separate channels over two speakers.

The album helped secure the appeal not only of stereo systems but also of Esquivel himself, who would remain in the U.S. for the next 20 years, as a recording artist for RCA and then Reprise, a contract composer for TV and film, and a long-term lounge act in Las Vegas. Along the way, the dynamic and innovative Mexican also attracted friends, colleagues, fans, women in and out of wedlock, and seven Grammy nominations.

Esquivel returned to his native land two decades later, but like even so many of the acoustic oracles of mid-century modern, he began emerging from the dust of America's used record bins before the turn of the millennium.

Steve Reed was among Esquivel's first crop of U.S. fans. As a Beverly Hills high schooler in the late '50s, he'd been listening to 'Other Worlds' on local station KMPC and searching for the artist's other albums. "There was nothing to which one could compare this," Reed, now 69, recalls of Esquivel and his music. "And it took a lot of courage from Esquivel, and from his backers, RCA, putting these heretofore unheard-of combinations of sound out there."

Esquivel's incomparability makes him difficult to describe, but Irwin Chusid, who has produced reissues for both the Bar/None and BMG labels, is well qualified to give it a try. "There was almost a musical Morse code in Esquivel's arrangements, where he would leave a lot of things out," says Chusid. "If Esquivel just put a couple of 'zu-zu-zus' and 'pow-pow-pows' and a couple of words [from the mouths of the Randy Van Horne Singers] which were a reduction from the original lyric, it was interesting that you would still know the song."

On record and in live performance, Esquivel's impact was fueled partly by his keyboard virtuosity, which he'd begun showcasing as a pre-teen, over Mexico City radio station XEW in the early 1930s. A few years later, the young prodigy was setting scenes for a popular radio comedian and learning to juxtapose the ranges and dynamics of different instruments.

Early on, he was subsuming his Latin roots within a more global sound, gleaned from shortwave radio. By the early '50s, samples of Esquivel's approach, which he'd christened 'Sonorama,' were being sent to New York by RCA's Mexican music director. Towards the end of the decade, the company decided to move this classy resource up north.

Young Steve Reed was thrilled when he found out "that I was going to have the opportunity to watch this genius" performing in a trio context at a West Hollywood club called the Melody Room. Within a few weeks, Reed, who was studying Spanish, was addressing his idol-turned-friend as 'Juan' and introducing him to Los Angeles and some of its denizens, including a Melody Room cocktail waitress named Joyce, who would become Esquivel's musical collaborator and second wife.

Possessed of seemingly boundless stamina, Esquivel held down a day job writing incidental music for Universal/Revue Studios TV shows, where his inherently dramatic approach to composition and arrangement were put to good use. He also composed the brief but perennially lucrative jingle that concluded each and every Universal TV production.