Plastic Fantastic Living - Page 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

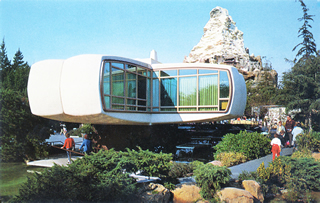

The House of the Future proved an exciting project for a pair of young architects who taught at MIT. Marvin Goody was 33, Richard Hamilton a few years older.

“The design team,” the architects noted in the MIT report, “was unencumbered by traditional solutions for enclosure of space and provision of living facilities.”

That’s not something you can say about every project.

Their charge was ambitious—not just to provide a market for plastics in homebuilding, but to do so in a way that was true to the material. Truth to materials is, of course, intrinsic to modernist thinking. “Simply substituting plastic for steel and wood was not enough,” the Associated Press reported.

“The ultimate form” of the house, the architects wrote, “had to be one that was peculiar to the plastics fabrication process.”

Also in line with modernist thinking was the social goal—to provide a functional family dwelling that could serve as a prototype for affordable plastic homes. “We hope this house may lead to a mass-produced plastic home,” Monsanto’s plastics division vice president Robert Mueller told the press.

Although the project cost $1 million, Monsanto pointed out that 90 percent of that amount paid for three years of research, not for the house itself.

Mueller suggested a commercialized version of the house might sell for $10,000 to $15,000—before hedging his bets. “Of course it may never be commercially available.”

Ernie Kirwan, then a graduate student of architecture in his 20s, came onto the project with dreams of his own. Socially progressive, he believed the House of the Future really was all about designing a prototype house for affordable living.

Kirwan worked on the House of the Future for seven months, starting in August 1955, drawing perspectives and elevations and making the model that caught the attention of the ‘Man Behind the Mouse.’

Kirwan admired his boss, Goody—a man of his own height, 6-foot-4, equally rail thin, a nice guy, quiet, almost taciturn, “very well thought of, an influential guy,” and a guy who enjoyed visual flair.

“Marvin had an eye for form-giving,” says Kirwan, now 85, who lives today only a mile from MIT. “He was more interested in the gestalt of the thing than its application. He was interested in powerful design concepts.”