Mid-Century Modern Art: Shag's World - Page 2

"It was his use of color," Shire says, "besides his amalgamation, combination, and adaptation of past influences and styles that he brought together. Josh did it in such a way as to be original and to make it seem new. He had the history and the language from the past, but he could put it all together. Most people have the influences, but they don't put it all together. And he has a very wry sense of humor."

"Most people call it 'Shag style,'" Agle says of the current vogue for neo-'50s art, "which is flattering to me. It's not so flattering to the other artists when people tell them, 'Oh, you're doing that Shag style.' I wanted to make sure I owned that style. I didn't want people to say, 'Your paintings reminds me of that other artist.'"

Shag has become so successful—his paintings sell at galleries for $10,000 and up, his prints in the hundreds of dollars, and he does not do commissions, thank you—that a wary observer might accuse the artist of cynically pandering to the mid-century masses.

As Shire noted in the book, 'Shag: the Art of Josh Agle,' "He has become arguably the most merchandised artist since Peter Max."

Could a Shag painting be seen as the equivalent of a Thomas Kinkade cottage but with a butterfly roof?

Not hardly. Nobody who spends any time with Agle could doubt his sincerity. The guy—despite his orange-tinged hair—is just too darned straightforward, and so obviously in love with what he draws. "I just paint the stuff I like and the stuff I'm interested in," he says.

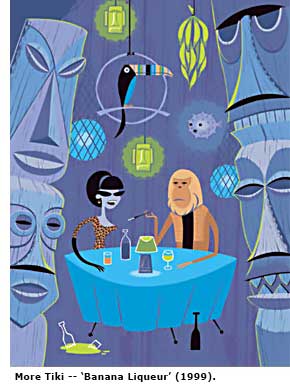

And Shag's art, far from being treacly and sweet, is sharp and colorful, cartoony—yet mysterious.

It also helps that Shag has his own vision of the era. "There was an optimism," he says. "When you bought a mid-century modern house and you filled it with modern furniture, you were looking forward, and I appreciate that optimism.

"And also to me, sophistication. Obviously most of the houses built in the 1950s weren't mid-century modern, but the people who were building them were more sophisticated, more artistic—and that's what appeals to me as well. And it also to me implies hedonism—the great cocktail parties, the smoking and the drinking. 'Playboy' magazine from the '50s and early '60s embodies that. It was okay to be a hedonist."

"I see the '50s as being mostly square, with little pockets of hipness," he says, "and it's those little pockets of hipness that really interest me."

"He just creates," says Lee Joseph, a record producer and deejay who knew Agle before he became Shag (the name blends 'Josh' and 'Agle'). "The market found him."

Joseph remembers when Agle would charge all of $175 for designing a band's entire look, its LP and CD covers plus posters. And Agle never sent a bill. "Josh," Joseph would say, "I really appreciate this, but you have to start charging me."

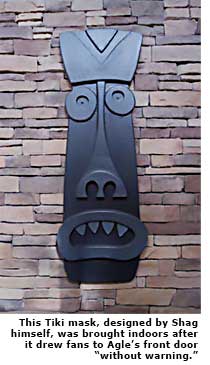

Agle himself got into modern design in a typically Southern California 1980s kind of way, by imbibing the Tiki ethos along with tropical drinks at his favorite Tiki bars, while picking up '50s and '60s LPs, chosen for their covers, at thrift stores in Santa Ana and Long Beach. Soon Agle was furnishing his apartment with mid-century furniture he found alongside the records.

One of nine children in a Mormon family that lived in Sierra Madre, in the mountains above Pasadena, Agle, who intended to follow his father's profession of accounting, did commercial art to pay for his studies—then switched his major to art.

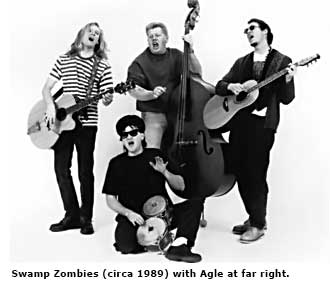

Meanwhile, Lee Joseph recalls, "The surf-lounge-exotica-garage genres were peaking, in kind of a cult sense," and Agle designed covers and posters in a variety of styles for such bands as Witchdoctors A Go-Go, Del Noah and the Mt. Ararat Finks, and the Brian Setzer Orchestra. Agle also worked as a record company art director, designing albums for Big Sandy, among others.

Agle also played lead guitar and sang with the Swamp Zombies ("a little bit rockabilly, some folk influence, a little punk," he says) and ran his own label, Mai Tai. He quit music in 2000. "Creatively," he says, "I was spreading myself too thin."

Agle focused on commercial art "because I knew that way I could make a living. I had friends in art school who wanted to be fine artists and ended up working at Aaron Brothers selling frames."