The Magnificent Moderniques of Mar Vista - Los Angeles - Page 2

Questions remain about how the rules would affect fences, landscaping, and the size of backyard additions. But about the big issues there is agreement. "No one wants second stories or tear downs or big front fences," Moreland says.

It is the streetscape, after all, that most unifies the neighborhood. Landscape architect Garrett Eckbo, who helped invent modern landscaping, set out rows of melaleucas, magnolia, Chinese elms and ficus. Much more than other modern tracts, including those by Joe Eichler, it is the landscaping that provides the unifying look. Although the developers did not provide parks, the idea was for front lawns to remain unbroken by fences to provide a park-like atmosphere. People still cherish that look.

Less successful, however, was the idea to provide communal backyards, undivided by fences. "That was Ain's vision," says Adamson, who has become the neighborhood's unofficial historian, "but it was not communicated well to the people who bought the houses. One of the original owners said (Adamson's voice takes on a huffy tone) 'We even had to put in our own fences!'"

But Ain and Eckbo did succeed with their fruit tree scheme. "They planted different fruit trees at different houses so people would exchange fruit and meet their neighbors," Michaelsen says. "We had plum and apricot trees when we moved in, and we did just that. Maybe that's how I got to know a lot of my neighbors."

Although the houses are largely identical, varying details and placement on the lot create a lively streetscape. Windows swing out to open. Clerestory windows bring in added light. Kitchens look out onto the street. "People like that because they know who goes where," Adamson says. Glass-filled doorways and walls open to backyards. Unlike many later modern tract homes, these don't use sliding doors.

"It's so peaceful, you know," Michaelsen says of her home. "Everywhere we look out, we see greenery."

Utility lines attach to houses discreetly, through rear alleys. A lack of street lights adds to the rustic air. Ain designed the homes using pre-cut studs and prefabricated cabinetry.

Inside, Ain proved that a small house, even at slightly larger than 1,000 square feet, can seem spacious—if not exactly big. "Finger-tip mobile walls convert the modern home to a choice of one, two, or three bedroom accommodations," the Modernique brochure promised original buyers. "Modernique design saves time, steps and energy."

In Michaelsen's model, the kitchen is to the left of the entry, the living room dead ahead, bedrooms to the right. Modernique homes bragged about their flexibility, and nowhere is that better seen than in the kitchen-living area.

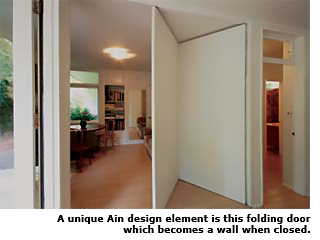

Modernique homes may have open plans. But they are open plans that can close up tightly—and cleverly. The main living area can serve as kitchen, living room, and dining room. Or the 'dining room' can be closed off via a folding door to become a master bedroom, guest room, or office. And to the rear of the house, a single large bedroom can become two smaller rooms by sliding a wall into place.

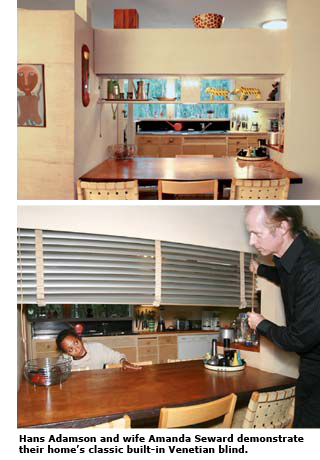

Cabinets divide the narrow, galley kitchen from the living room. A pass-through between kitchen and living room functions as the home's command-and-control center. "The center of the house is this table," says Bonnie Jones. "If anyone wants to sit down and do any work, this is where they sit." When Max and Rita Lawrence founded the modernist firm Architectural Pottery in 1950, it was on this table that they threw their pots. The kitchen can be shut off from the living room using built-in Venetian blinds to hide the pass-through.

"I don't think there's a better-designed small house that can be used with as much versatility as these," says Amanda Seward, who helped the neighborhood win its historic designation. The various folding and sliding doors do not, however, provide much sound insulation.

Ain and Eckbo clearly succeeded in their goal of creating a family-friendly neighborhood. It was a great place to grow up, Barbara Jones remembers. Kids played ball in the streets. Were the houses too small for families with children? Residents, some of whom raised three, laugh. Michaelsen asked her two children if they ever felt cramped.

"They said, 'We were never in the house; we were always playing outside,' which is true. They didn't spend time in their room. My youngest son, he's a realtor, he said, 'Mom, times have changed, because kids today have a computer, they have a television, they have whatever games there are, so they spend all their time in their room. We didn't.'"