Loving the Highlife in Crestwood Hills - Los Angeles - Page 2

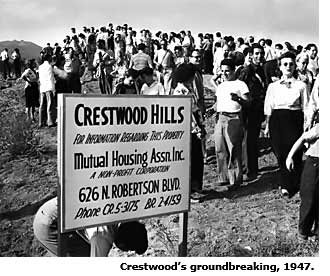

Zellman and Friedland believe the neighborhood has national significance as well, as "the largest modernist residential cooperative ever attempted in America."

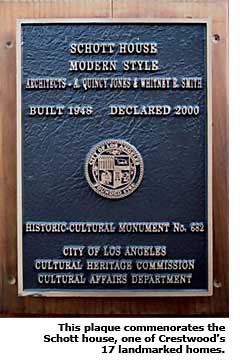

In 2002, the Los Angeles Conservancy gave Buckner its Preservation Award for helping preserve the homes.

The people whose homes have been landmarked don't mind the extra controls. For one thing, they qualify for property tax reductions under the state Mills Act because their homes are a protected historical resource. Plus, they simply love their homes and wouldn't want to alter what makes them special. "We're a designated cultural-historical landmark," O'Neal brags. "You can't mess around with your house." Landmarking doesn't prevent alterations or additions, Buckner says, if they are done sensitively.

"People didn't see any value in the homes," Buckner says. "Now there is respect for the architecture."

But not among everyone. In September 2007, just before the MAK Center for Art and Architecture led an architectural tour of the Crestwood Hills, one of the last remaining homes was demolished by its owner—which dropped the number of intact residences to 30. Fans of the homes were aghast. The house was replaced by a basketball court.

But the architectural review board of the Crestwood Hills Association had its hands tied, says Allison Baratelli, a longtime member of the homeowners association.

Gregory Serrao, a member of the three-person architectural board, says they lack "legal basis for stopping demolitions" in the neighborhood's governing covenants. "We have jurisdiction only over new construction and changes. If somebody buys a Quincy Jones house and wants to tear it down, there's nothing we can do. That's just a fact."

Baratelli, who brags about the welcome wagon that greets neighborhood newcomers, argues that despite rifts over architectural controls, Crestwood Hills is a great place to live. On that point, she gets no argument.

"Raising a child in this neighborhood is like the old-fashioned days of walking to school and walking to each others' homes," says Kathy Leader, who has a 13-year-old daughter and nine-year-old son. The preschool—which is still a cooperative, as it was when Nora Weckler was its first president—helps create a tight-knit community, she says.

It's always been a great place for children, says Peter Israel, who grew up in the neighborhood, and whose father was a longtime board president. Israel remembers adventuring through the hills. "I was in the wild," he says.

Shortly after moving to the neighborhood, Kathy and Jon Leader helped revive the tradition of hosting concerts in woodsy Crestwood Hills Park. They've featured jazz, African dance, and klezmer. The park, once owned by Mutual Housing, was donated to the city, and is another community-building spot, thanks to pizza nights and the like.

Crestwood Hills, in other words, retains much of the spirit of its cooperative days. Even the mix of people is similar to the old days—Hollywood writers, musicians, photographers, graphic designers, lawyers. The big difference today: owners have fatter bank accounts.

"When it was originally built, this was an affordable neighborhood to live," says Christopher Wargin, a designer of motion picture graphics who serves on the Crestwood Hills board. Most of the homes were small—many only 1,200 square feet—with small galley kitchens and bathrooms that, by today's standards, seem cramped.

Lizzy Bentley O'Neal's house is typical. Low-slung, with a free-form plan, resting on a pad well below street level, the post-and-beam home comes across as rustic and unpretentious. The exterior is vertical redwood siding above concrete blocks. The front door hides beneath a canopy that's supported by broadly cantilevered roof rafters.

Out back the house opens up, with a wall of windows beneath a glassed-in, low-sloped gable. Inside are open ceiling beams, a narrow hallway to the bedrooms, and concrete block walls that create a raised dining area over a sunken living room. "This was not a glitzy place," O'Neal says of her home. "The master bath doesn't even have a tub."