Greater Sacramento Strengs: Valley of the Atriums - Page 2

Sparks wasn't always so easy to convince. People who knew Sparks throughout his career said he would never build something that wasn't modern—and would never compromise on design principles or quality. He became the Strengs' modernist conscience—from day one. Bill remembers bringing him to their first development, Evergreen Estates subdivision in Sacramento, to show off a model home. The front of the ranch house had brick below and cedar siding above. The rear was all stucco. "Carter sat there shaking his head," Bill remembers, "and Jim and I looked at each other, 'What did we do wrong?'" Sparks used materials consistently—"If it's good enough for the front [of the house], it's good enough for the back," he told Jim.

"He had definite ideas about what was right and wrong," Bill says. "When we were selling these houses," Bill says, "we became believers. We were able ourselves to tell people, 'No, Carter wouldn't permit that—and you wouldn't want it either.'"

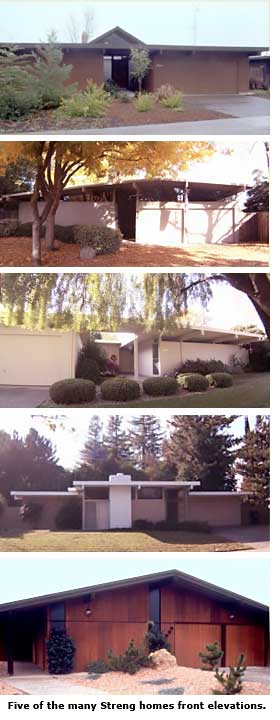

Sparks designed what the Strengs call 'the Carter classic,' a flexible plan that could include three or four bedrooms, and an open-plan living area blending living room, dining, and kitchen. Different roof lines and elevations provided variety while using the same basic plan. The main living area had walls of glass with sliding-glass doors opening onto a backyard, and bedrooms with high transom windows for privacy and light. Living-dining rooms had high ceilings—up to 13 feet—often with beamed ceilings following the roof line.

Particularly popular were the atrium designs. Many owners filled the atriums with gardens. At least one installed an indoor waterfall. The Strengs offered a flat-roofed model as well as the 'transitional,' so-called because its low-pitched gable roof—the gable ends filled with glass—recalled the more traditional ranch. It proved their most popular home then and remains so today.

Most homes were sold before they were built, and many were customized for the buyer. Sparks worked with buyers to make sure the changes fit the architectural style. Most homes ranged from 1,800 to 2,200 square feet. The Strengs also built half-plexes—smaller attached homes, about 1,300 square feet.

Interior touches included the same spherical lighting fixtures used by Eichler, exposed concrete aggregate floors extending from the outside in, and rectangular redwood and plastic light fixtures designed by Sparks. Bill and his wife Karmen, a quiltmaker, have lived in their Carter Classic, expanded to 2,200 feet, since 1975.

The homes Sparks designed for the Strengs shared many characteristics with his custom homes. "You could see what he did when he wasn't working for cheapskates," Bill jokes, showing off one of Sparks' custom homes in the El Macero neighborhood of Davis. The home is a spectacular composition of glass, broad stone piers, steel fireplace, wooden beams, and shingled, low-pitched Craftsman-style roof. Angled glass walls artfully bring the outdoors inside—and make it hard to tell which is which.

"We were trying to capture what he did at a cut rate," Bill says. But Sparks wasn't always interested in cut rate. He asked for brushed aluminum doorknobs and they agreed. Then he asked for brushed aluminum hinges instead of the standard brass. "I told Carter, it's not worth 50 cents extra per door. Nobody will notice them," Jim says. "He said, 'I'll pay for them.' He shamed us into it."

Other aspects of Sparks' design saved the Strengs money, however, including cathedral ceilings that shared joists with the roof, sparing the cost of an attic. And the modern homes had no need of "fake shutters or curlicues," Bill says. "Hiring an architect didn't cost us money," Jim says. "It saved us money."

Working with Sparks, however, could be challenging. Sparks loved the creative side of architecture. "When he was inspired," Bill says, "he could work prodigiously. I could state as a fact he was a genius." But he wasn't inspired when it came to churning out working drawings or handling paperwork. This proved tough for the Strengs because Sparks, who was never their employee, generally ran a one-man office.

"Sometimes he didn't get things done," Bill says. "He spent an awful lot of time at the coffee shop socializing with his neighbors," Bill says. "Jim would go over and drag him out of the coffee shop, sit him down at his desk. Jim would sit outside and would answer the phone and say: 'Carter's in conference.' " The Strengs finally hired architecture students to do working drawings, under Sparks' direction.