Dance of a Lifetime - Page 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"The light was nothing but the full moon, so it was very beautiful."

Few dancers are as serious about their work as Anna Halprin—not least in the scientific sense. At the educationally progressive University of Wisconsin, in the 1930s, she studied with mentor Margaret H'Doubler, not just dance but kinesiology, human movement, bones, muscle. When Larry, whom she met at the university, attended one of her classes that involved dissecting a human cadaver, he fainted.

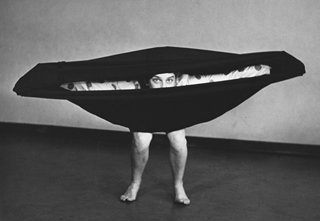

Yet Halprin began her performing career best known for her "deadpan comedy," in the words of poet, filmmaker, and her frequent collaborator James Broughton. An "incredible clown," he called her, "absolutely hilarious." Dance historian Janice Ross compared Anna to "another curly-haired, red-headed comedienne," Lucille Ball.

Halprin, who at 94 still taught almost daily on the dance deck of her Mountain Home Studio, a good 70 wooden treads below the level of her home, works with a model of a human skeleton. "This is our instrument," she tells her class. "We can't go out and buy a new body."

A poor student in her girlhood but good at sports and immersed in dance, Ann Schuman began teaching her friends dance at age 12 and figured early on she would make her life work as a dance teacher.

She has.

Never interested in ballet ("everybody laughed at me," she recalls about her first ballet class as a girl), she gravitated to modern dance instead, impressed by Isadora Duncan. She briefly danced for Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman, two pioneers of modern dance, in the Broadway show 'Sing Out, Sweet Land,' with Burl Ives singing 'Big Rock Candy Mountain.'

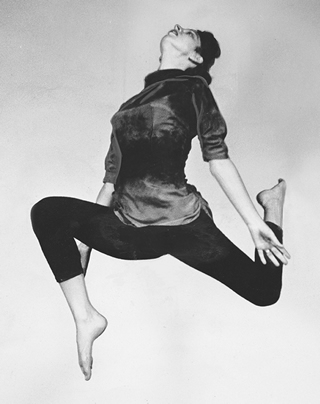

But she turned away from modern dance, complaining the choreographers were developing "a very rigid style."

Their choreography, she says, "was very hierarchical. It was very personality oriented." Humphrey, Weidman, Martha Graham would create movement and instruct their dancers to do it.

"I'm not interested in choreography. I'm not interested in other people creating my vision," Halprin says.

Instead, over the years, Halprin had developed her own ways of generating dance, starting with what she called "task oriented movements," building something, or carrying something—wine bottles, say—or walking up and down hills. "Everyday movements that everybody could identify with," she wrote.

"That was a way to get away from the preconceived styles," Halprin says. Halprin often started with improvisation—which was not part of professional dance in the 1940s or '50s.

Dancers come from different backgrounds, have different ways of moving, of thinking. Their natural movements should contribute to the dance, she argues. "Anna preferred that movement have its own meaning rather than stand as a symbol for something else," Ross wrote, adding, "and the way she arrived at this meaning was through guided improvisatory work."

Halprin also addressed different subjects than other dancers, and in different ways. She focused, she said, on "real life themes," on "dances...[with] a real purpose in peoples' lives."