Breaking the Rules

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It was a marriage no matchmaker would have proposed—the coming together of one of America's largest and most architecturally conservative homebuilders with two of America's most progressive modern architects.

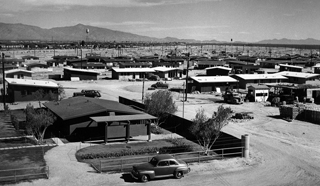

But for a time in the late 1950s, Levitt and Sons, builders of thousands of Colonial and Cape Cod-style homes in a succession of Levittowns on the East Coast, worked with A. Quincy Jones and Frederick Emmons to develop a new Levittown like the world had never seen.

In hiring the Jones & Emmons architectural firm, Levitt was hiring men who were activists as well as designers, pushing throughout their careers against what they saw as outmoded habits of designing neighborhoods, and against zoning rules that enshrined poor planning.

Their goal, rooted in the late 19th century Garden City Movement, aimed to create 'total communities.' Jones & Emmons called for a planned environment, providing everything from the macro—access to transit, shopping, community centers, parkland—to the micro—built-in furniture, shade shelters for card games, paths for wheeled toys, and crawling tunnels for children.

Jones & Emmons strove to create neighborhoods with varied streetscapes, winding greenbelts, mini-parks arrayed behind homes, and streets designed for safety.

"The facilities to learn, worship, work, and play are all part of living," the partners wrote in their 1957 book Builders Homes for Better Living. "The best home is a part of a total community."

It was a goal shared by many progressive architects and landscape architects throughout the 20th century, including Clarence Stein and Henry Wright, who designed several communities along these lines, including Radburn in New Jersey and Baldwin Hills Village in Los Angeles.

Jones & Emmons also inveighed against builders whose sole goal seemed to be "getting the greatest number of lots per acre," and noted, in an almost offhand way, that homebuilders "have a moral obligation to provide a pleasant place to live."

Today, A. Quincy Jones (1913-1979) is best known among the public for his often astounding, sometimes palatial, custom homes, including the Walter Annenberg Retreat at Sunnylands in Rancho Mirage.

Among Eichler homeowners, of course, he's best known for designing thousands of Eichler homes and laying out many Eichler neighborhoods, including Greenmeadow in Palo Alto, the first with a community center and central green area.

Jones & Emmons also designed college campuses, offices and factories, and much more.

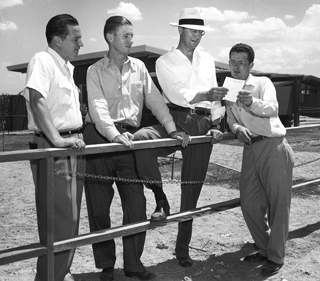

Often overlooked, however, are the dozens of tract homes Jones designed for a host of homebuilders other than Eichler, ranging from Del Webb in Tucson to Hallberg Homes in Portland and Don Drummond in Kansas City, where Quincy Jones was born. By 1966, according to Jones, in an interview with writer Paul Heyer that year, more than 5,000 homes had been built to his designs.