Art Goes to Pieces - Page 3

Both King and Sizemore say modern mosaics make a fine fit for mid-century architecture. “My home is my ‘gallery,’” Sizemore says, “and mosaics look great in an Eichler setting.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

From its beginning in the ancient world to its triumph in medieval Ravenna and Venice, mosaics have traditionally been used for floors and walls in homes, shops, and religious and public buildings.

Supplanted by paintings during the Renaissance, mosaic returned in the 18th century when the Vatican established a workshop to produce long-lasting mosaic versions of religious paintings—a practice later mosaic artists pilloried for producing characterless work that merely aped another art form.

What Vatican-trained artists created, Peter Fischer wrote in his 1969 book Mosaic: History and Technique, were “neither true paintings nor true mosaics.”

|

|

|

True mosaics are nothing like paintings, enthusiasts say. Instead, they are all about light and reflection, and the magical push and pull between the overall design of the work and the hundreds or thousands of fragments that make it up. Artists cut up ‘smalti’—Italian colored glass, ceramic, or other materials—to create rich textured surfaces.

Sizemore says, “The elements catch the light. They throw light in completely different ways than paint would. Some material reflects light, some absorbs light. You have a syncopated kind of surface that is a wholly different language than painting.”

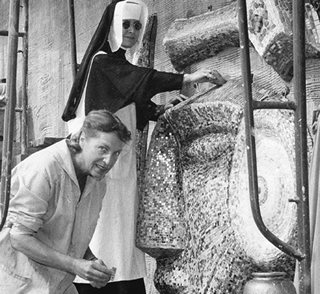

That’s why many modern mosaic artists prefer putting together their mosaics themselves, as opposed to having one artist design the work and others assemble it. Still, mosaics, like film or theater, can succeed as a collaborative art, with the craftspeople providing the textures of the tesserae.

|

|

|

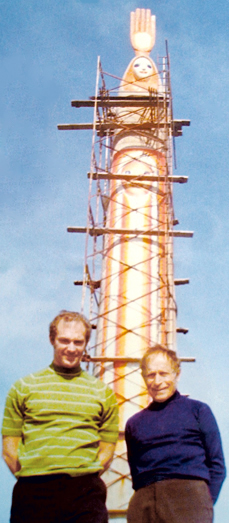

The current revival of mosaics is far from the first. In 1898, in Architectural Record, mosaic artist Lewis F. Day wrote about such modern artists as Burne-Jones and Walter Crane taking up the art. Antonio Gaudí, working in Barcelona in the late 19th century, used tile, glass, broken toys, and other objects in mosaics that were an integral part of his buildings, including the church Sagrada Familia.

During the Depression, as part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal that put millions of American back to work, mosaic murals were produced by artists working with the WPA.

In Long Beach, what was billed as “the largest mosaic tile mural in the world…the size of the average five-room house,” a beach scene of lifeguards, bathers, sailboats, and dogs filled a wall of the municipal auditorium. It was done by Henry Nord, Stanton MacDonald-Wright, and Albert King.